In this history lesson we are going to describe a phenomenon that happened in traditional finance between 1997 and 2000 and another one very similar that happened in the crypto market between 2015 and 2018. In the first case, we have the “IPO mania” and, in the second case, the “ICO mania“.

During the IPO mania and ICO mania, financial markets experienced a real “bull run“: an expression, also known in traditional finance, that in the crypto sector refers to the formation of a speculative bubble that begins with the exponential rise in the price of Bitcoin before the so-called halving. The halving is an event that occurs every 4 years and basically the amount of bitcoin issued upon validation of each blockchain block every 10 minutes is cut in half automatically.

TRADITIONAL FINANCE

HISTORICAL AND ECONOMIC CONTEXT

The 1990s was a period of robust economic growth, especially in the United States. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the default of the USSR in 1991, the U.S. economy faced virtually zero geopolitical risks, relatively low interest rates, low inflation, and rapid technological innovation.

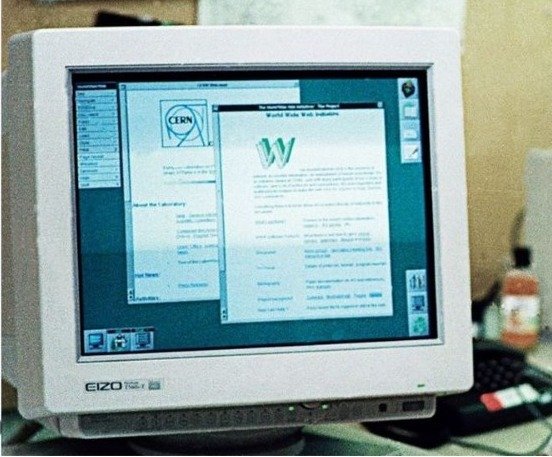

Also in 1991, the release of the world’s first website from CERN in Geneva by computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee shook the world, as that event led to the creation of numerous technology startups, which sought to introduce innovative products related to the Internet and digital technologies into the economy. The new millennium was just around the corner, and many people believed that they would find the idea that would change the economic-financial paradigm and – in some cases – the entire world.

The favorable conditions were also supported by a very relaxed regulatory environment, which facilitated access to the financial markets: a process of “deregulation” of U.S. finance had been underway since the mid-1980s, which, combined with the introduction of new trading and financing techniques, produced a steady increase in the interest of investors and speculators.

IPO MANIA

An “IPO” is technically an Initial Public Offering, a process through which a private company sells, for the first time, its shares to the public, transforming itself from a private company to a publicly traded corporation. The main purpose of going public is to gain access to large amounts of capital, but there are high costs of listing and costs arising from disclosure requirements (publication of financial statements).

The IPO mania reached its peak in the mid to late 1990s, with an unprecedented number of companies listing in the financial markets, especially in the technology sector. Enterprises involved in the Internet and Web 1.0 themes promised explosive growth despite often having very poor earnings (or even net losses) at the time of IPO; some of those failed the test of time, such as Netscape (IPO in 1995), while others managed to build a successful business and prosper, such as Amazon (IPO in 1997).

In many cases, the influx of large amounts of capital enabled many technology companies to expand rapidly, investing in research and development (R&D), marketing, and international expansion. This led to innovations that had long-term effects on the economy, transforming various sectors such as commerce (e-commerce), communications and entertainment. The idea was to build the “New Economy.”

The IPO boom led to exponential growth in the stock market, but it was the Nasdaq100 index that performed the most incredibly: about just over 1000% from 1995 to 2000. The Nasdaq100 index – the picture below represents the speculative bubble period – is a financial instrument that tracks the performance of the 100 most capitalized technology stocks (referring to companies such as Apple, Microsoft, and so on) on the U.S. stock exchange.

Investors and speculators, attracted by the potential lavish profits, often bought IPO stocks without conducting careful fundamental analysis. Since many of those companies listed through IPOs had been founded in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was indeed almost impossible to invest while adhering to the classic criteria for analyzing a listed company, such as profitability, growth, financial position, dividends, and price history, because there was not enough history to analyze.

All these factors, combined with the lack of proper regulation, contributed to the formation of what was later called the “dot-com bubble” or the “Internet bubble.”

GROWTH AND BURSTING OF THE BUBBLE

The new millennium was approaching and some market participants realized that:

- Many business models were unsustainable, i.e., they continued to experience even severe net losses;

- Investors and speculators were buying technology stocks driven by FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out);

- Liquidity in order books was beginning to run out, a sign that prices were too high to justify new capital allocations;

- Managers of those companies newly listed through IPOs were either incompetent or were merely interested in the growth of the company’s own stock price, thus not aimed at the company’s long-term success.

In addition, Alan Greenspan, the chairman from 1987 to 2006 of the Federal Reserve, which is the central bank of the United States, raised interest rates from 3.0% in 1993 to 6.5% in 2000 because the economy – as described above – and the U.S. financial markets had overheated and the risk of reawakening inflation, which the had been experienced in the 1970s, had increased. By raising interest rates, the present value of companies’ future cash flows fell sharply and the cost of debt rose considerably: a fatal combination that crushed the IPO craze.

In March 2000, the dot-com bubble burst, leading to a drastic drop of the stock market and the bankruptcy of many technology companies. This had a domino effect on the real economy as a mild economic contraction occurred.

The Nasdaq100 technology index slumped -83% from its high in March 2020 to its low in October 2002. The Federal Reserve decided to lower interest rates from 6.5% in the summer of 2000 to 1% in the fall of 2003 to support both the economy and the markets. For example, the stock price of Cisco Systems Inc. (CSCO), one of the leading technology companies at the time, went from $5 in 1997 to $82 in 2000, an increase of about 1,500%; however, CSCO recorded a -90% from 2000 to 2002.

The IPO mania of the 1990s was a period of intense activity in the financial markets and significant transformations in the real economy. While it led to remarkable innovations and economic growth, it culminated in a speculative bubble that caused serious consequences when it burst. Despite the failures of many companies, the foundations laid during this period continued to positively influence the digital economy in the following decades.

CRYPTO SECTOR

PRE-BULL RUN PERIOD

About 20 years after the dot-com bubble, mutatis mutandis, a new sector of very high technological innovation made its way into the world: cryptocurrencies. It all began with the launch of Bitcoin in late 2008 and early 2009, a time when the crypto sector was virtually nonexistent. During the first bull run of Bitcoin’s price, some very relevant events happened:

- In 2010 the Mt. Gox exchange was founded, which at the time was the largest by trading volume;

- In 2012 Ripple (XRP), the first and biggest centralized cryptocurrency, was launched;

- In 2013, Dogecoin (DOGE), the world’s first memecoin, was created;

- In 2013, the Grayscale Bitcoin Trust (GBTC), the first financial product suitable for institutional investors, was issued.

2014 and 2015 constituted a period of major declines for the price of Bitcoin, which in fact recorded roughly -85% due to a hacker attack on the Mt. Gox exchange, from which more or less 850,000 bitcoin were stolen. That event represented a very hard hit on investors’, speculators’ and developers’ confidence, but the market managed to recover after some time.

An important vehicle to facilitate the expansion of the crypto sector was the launch of Tether (USDT) in 2014: the first stablecoin in the crypto sector by trading volume, which allowed investors and speculators to easily trade bitcoin and altcoins and enabled centralized and decentralized exchanges to offer more services than before.

ICO MANIA

The “ICO mania” (Initial Coin Offering) developed particularly in the 2017-2018 biennium, a period marked by the emergence of a large number of new innovative start-ups and a speculative frenzy that attracted the attention of professional and non-professional investors from around the world. ICOs, similarly to IPOs, are a fundraising method still used today, such that startups obtain funding by issuing new cryptocurrencies/tokens, based on their blockchain, by receiving bitcoin or ether, which are universally accepted assets in the crypto industry, from initial investors in exchange for the cryptocurrencies/tokens and eventually these new coins are launched in the market. Following the listing, if the project the developer team proposed was deemed viable by market players, the price of the cryptocurrency/token in particular skyrocketed.

The number of ICOs launched in the market soon became exponential. Many startups used the ICO vehicle as a way to bypass traditional and slower funding methods; according to some reports, ICOs raised over $6 billion in 2017 alone.

Thus began a self-reinforcing process that led to a speculative bubble that reached biblical proportions for the time. Bitcoin and Ethereum were the main mediums of exchange in the crypto sector at that time, so the bull run started precisely from the exponential rise in the prices of those two main cryptoassets by capitalization, after which liquidity flowed to ICOs.

The “altcoin” market was officially born. In theory, an “alternative coin” is a digital currency created to replace Bitcoin, an asset that many industry enthusiasts felt was now technologically obsolete. Despite this, many altcoins had goals other than to replace bitcoin: in the bull run of 2020-2021, the use of altcoins shifted from replacing bitcoin to developing new sectors, such as the metaverse, gaming, and NFTs.

Unfortunately, as the crypto sector was poorly regulated in 2015-2018, many ICOs turned out to be frauds or projects with no real technological-commercial value. The practice of raising money and disappearing with investors’ money became so famous that it was given a name, namely “rug pull,” which literally means “pulling the rug/carpet from under your feet”.

As expected, the unchecked growth of ICOs attracted the attention of regulators around the world. Countries such as China and South Korea took drastic measures, banning ICOs and imposing strict regulations to protect retail investors. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) also intervened and classified many ICOs as unregistered securities offerings.

Despite the problems and fraud, some ICOs were successful and enabled the development of major projects and platforms in the cryptocurrency industry. For example, Ethereum itself was funded through an ICO in 2014, and many of the 2017 ICOs focused in the field of decentralized applications (dApps). In the same year, the ERC-20 standard was created and the procedure for creating a cryptoasset on the Ethereum blockchain was codified: the launch of MakerDAO was an example, as DAI, the first stablecoin based on the Ethereum blockchain, was introduced.

The ICO craze period of 2017-2018 was a time of tumultuous growth and speculation in the cryptocurrency sector, which produced both positive and negative lasting effects on the market. Cryptocurrencies demonstrated to the world not only their potential as a technologically innovative asset with a volatile price, but also the need for regulation and investor protection.

Interestingly, the linear graph of Bitcoin’s price in the ICO mania is very similar to that of the Nasdaq100 index in the IPO mania.

END OF BULL RUN AND CAPITULATION

The price of BTCUSD (the chart representing the price of Bitcoin expressed in U.S. dollars), starting from $150 in January 2015, touched an all-time high at the time in December 2017 at about $19,500 (an increase of +12,800%), while Ethereum, which started from $0.4 in October 2015, marked the top in January 2018 at $1,420 (+335,200%).

However, every speculative bubble is bound to burst, as no market trend (bullish, bearish, sideways) lasts forever.

In the case of the bull run of 2015-2018, the euphoria ended abruptly with the momentous “sell the news” following the SEC’s approval of the CME Futures Bitcoin ETF: for the first time in the history of the crypto sector, mainstream finance had concretely signaled its intention to integrate the world’s most important cryptocurrency into the financial system, and it did so through a product suitable for institutional investors, namely a fund tradable on the Chicago Merchantile Exchange, a U.S. exchange specializing in derivatives.

Given that financial asset prices generally never fall slowly, the price of a bitcoin in U.S. dollars lost -84% in just 12 months, from December 2017 to December 2018. Ethereum fared worse: it recorded -94% from January 2018 to December 2018. Almost all altcoin prices lost -90% to -100% from their all-time highs, and many of them never recovered.

What really triggered the bear market of 2018? At the end of 2015, the U.S. central bank (Federal Reserve Bank) interest rate was near zero. Just like in the IPO mania period, interest rate hikes cooled down the frenzy in financial markets: in January 2019 it reached 2.5%. After 7 years of expansionary monetary policy, the Fed, following ZIRP (Zero Policy Interest Rates) and QE (Quantitative Easing, which refers to a plan to inject liquidity through the central bank’s purchase of bonds), had begun a new “tightening cycle,” i.e., a new cycle of interest rates hikes, but financial markets were not ready.

It was not the change in the context of financial markets but a devastating event the cause of the beginning of the bear market (a bearish trend price that lasts for many months, even years) of 2018. From the early days of January 2018, the VIX, the volatility index of the S&P500 stock index, began to rise faster and faster each day, until it reached 50 points on February 6, 2018. Generally, the higher the value of the VIX, the more stock prices fall. Well, the 40-point level is universally regarded as a value that indicates the presence of panic among market participants, so reaching 50 points represented a truly extreme event. In fact, during the same period, the S&P500 index recorded -12% from all-time highs in only 6 trading sessions. As the following image shows, years and years of low volatility allowed a feeling of greed and complacency to work its way into the minds of investors and speculators, until reality hit unexpectedly hard.

In mainstream finance, that collapse in the first two months of 2018 came to be called “Volmageddon,” or the Armageddon of volatility, which had exploded not only for fundamental reasons, such as higher interest rates, but also because of market participants’ over-exposure to options: simply put, most were betting that volatility (VIX) would remain low indefinitely, but markets always surprise the unobservant.

Bitcoin, an asset that was starting to correlate to the classical markets in terms of price action, had hit all-time highs in mid-December 2017 due to the approval and launch of the Futures ETF at the CME and found a major local bottom about 50 days later: in the very first days of February 2018, totaling -70% from the all-time high. That was the first leg-down of bitcoin’s price, which was followed by a 100% rebound and subsequently the downtrend continued until December 2018.

COMPARING EPISODES

The U.S. stock market and the crypto sector have once again proved to be interesting environments for studying the human nature, which has been unable to break out of the endless cycle of fear and greed: as in a hellish loop, asset prices rise first slowly then quickly and the same process repeats itself for euphoria in the minds of investors and speculators. After that, a brief period of complacency is experienced, during which prices begin to reverse bullish trend, eventually the speculative bubble bursts and the initial fear is followed by panic.

In two distinguished circumstances, separated by 20 years, a series of conditions favorable to the proliferation of start-ups and enterprises that had little or zero real-world utility and listed themselves on financial markets to seek financing occurred. Many people succeeded in changing their lives with the profits generated by their investments, but the subsequent losses were extremely severe. Relaxed regulation, the arise of an innovative technology sector, and a decisivly expansive macroeconomic environment provided the perfect mixture for an Internet-based speculative bubble and a blockchain-based one.